Few historic artifacts, perhaps, are as delicate and as laden with sentiment as mourning jewelry. With its roots in Sixteenth Century Sweden, the practice of hair weaving often found in these uniquely beautiful, albeit rather morbid, pieces retains its enchantment today. The exchange of hair as a token of love goes back to the pharaohs and queens of Ancient Egypt. The fragility and beauty of hair inspired the creation of jewelry in England and France in the early Eighteenth Century. Such pieces were worn as reminders of loved ones who had passed on, and exhibited the meticulous diligence of their creators, who wove the thin strands into braids and created intricate designs. Even art and literature suggested that women’s hair possessed magical qualities and suffused it with symbolic meaning.

Clicking on the examples throughout this post will redirect you to their sources (provided the examples are not privately owned or from expired auction listings, as is the case with many which link to Pinterest).

The notion of hair as sentimental was popularized in England in 1861, when the death of Prince Albert compelled the grief-stricken Queen Victoria to permit only dark attire at court. The distraught monarch took to wearing jewels with locks of her late beloved's hair, and the fashion was soon emulated by other mourners. It soon spread throughout England and eventually across the sea to America, where during the Civil War military wives treasured locks of their departing husbands’ hair. From the 1850s through the 1880s, hairwork was all the rage. Women were so enamoured with the pieces that they purchased kits to craft their own from the hair of their husbands and children. Indeed, the cultural significance of hair mementos was made evident in written works such as Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock and Jane Austen’s treasured novel Sense and Sensibility.

Hair, though the most popular medium in the creation of mourning jewelry, was not the only material employed. Many designs were set against ivory. Some were framed by gold; others featured onyx or enamel. A myriad of adornments were used, as well; among them pearls and gems like diamonds, emeralds, amethyst, sapphire, and topaz. Just as the materials in the pieces varied, so too did the types of pieces themselves: Not all mourning pieces were brooches; lockets, rings, and miniature portraits also proliferated.

The creation of hair tokens required scrupulous preparation. For the hair to be properly preserved, it was boiled in soda water and then carefully divided into groups of twenty to thirty strands. Besides jewelry, hairwork spawned a number of creations, including bracelets, rugs, and furniture. The dawn of the Industrial Revolution and shifting views about the importance of hygiene saw the crafting of hairwork decline in the late Nineteenth Century, as new means of production and a waning emphasis on sentimentality brought the practice to an end. Nonetheless, a fascination with extant examples prevails among collectors and admirers today.

The album above (click on the arrows to scroll through the pages; click on the pages to enlarge), from the NY Public Library Digital Gallery, exhibits just how infinite the possibilities were for designing mourning jewels. The symbolism employed was often derived from the artwork of the time. Brooches made art more accessible to the public, as people could fathom connections between imagery in their jewelry and artwork in museums.

Natural symbolism can be seen across the whole history of mourning jewelry. The poppy, for instance, holds the timeless message of remembrance of loss through conflict (indicated by its blood red colour) and has been found everywhere from Egyptian tombs, to Roman shrines to Demeter and Diana, to present day war memorial ceremonies. The poppy also provides seeds for opium, a remedial drug for insomnia. Thus, the poppy has long represented both blood and sleep, two things closely tied to death.

The forget-me-not is eponymous; a popular symbol in neoclassical jewelry, it was often utilized after the world wars, conveying a clear message with its very name. The cypress, considered a mourning tree by the ancient Romans, is often seen in the background of neoclassical jewelry behind its less somber sister, the willow. The cypress casts a dense and dark shadow over gravestones, and its unique shape points skyward, directing the viewer’s eyes to the heavens and to the importance of the after-life. The dainty and pure daisy alludes to youthful innocence, and, like the lily, is found in pieces mourning the loss of children and unmarried women. The weeping willow has certainly earned its name: The tree is the most common botanical symbol in mourning jewelry. It seems to empathize with the mourner, as its shape resembles a hunched, crying figure, and its leaves look like tears.

In terms of the animal kingdom, birds were popular symbols for their grace and heavenly nature, qualities enhanced by their ability to fly high and far. The dove, however, was perhaps the most common bird in mourning pieces. Its pure white feathers symbolized an immortal soul. It also had connotations of peace and hope, specifically when it was depicted carrying an olive branch. Doves were often manifest as lovers, offering comfort to the living that their immortal soul would always remain with the deceased. They often had religious connotations, and sometimes represented the Holy Spirit. Peacocks also feature in mourning brooches, and are perhaps one of their more intriguing and complex symbols, with roots in alchemy. The point at which a metal’s purities are removed and gold is on the verge of formation is known as ‘cauda pavonis’, which literally translates into what we know as a peacock’s tail. The inclusion of a peacock's tail, then, symbolized that just as every metal holds the potential to make gold, within each soul (once its impurities are removed), there is a golden and pure soul waiting to be uncovered. Peacocks represented this moment of unity between man, nature, and the divine.

Certain objects suggested the macabre and the morbid. An upside-down torch represented abandoned hope and the struggles of a life without light. Conversely, a torch, when right-side up, was a symbol of guidance through life’s dark moments and of enlightenment and intelligence. The hourglass, skulls, and skeletons acted as memento mori; they suggested that time and one's lifespan were ever elapsing, and prompted individuals to act in a manner that would be judged positively by God. Columns, found predominately in neoclassical jewelry, stood for various things: a broken column represented a life cut short, and an unbroken column was a strong pillar of eternity and unconditional love from which mourners could derive support. The presence of drapery atop a column signified death, and upright columns pointed toward the heavens comforted mourners with their reminder of eternal life. A more obvious symbol was the urn, an object hearkening to the deceased and associated memories. These were typically placed at the forefront of imagery on brooches, with their prominence emphasizing their relative importance.

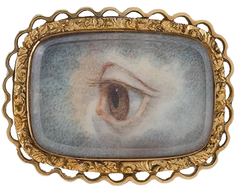

Unsurprisingly, another recurring theme in mourning jewelry was eternity, most often represented by the serpent, the belt, or the knot. Serpents were typically shown consuming their own tail to suggest eternity, rebirth, or immortality. They could also represent the deceit that transpired in the Garden of Eden, serving to remind the wearer of his sins. Belts might loop around themselves, symbolizing eternity, fidelity, and protection. The belt buckle strengthened the eternal bond between souls, and provided a sense of support to the wearer. Knots were often accompanied by a dove and the saying "the further apart, the tighter the knot"; just as a knot tightens and becomes stronger when each end is pulled, the eternal bond between two people (often lovers) is usually strengthened by death, rather than weakened by it. A Celtic mystic knot, though comparatively uncommon in mourning jewels, alluded to the idea of birth and rebirth into the eternal world. Other common symbols included arrows and quivers, trumpets, eyes, and the trinity of the cross, the heart, and the anchor. Arrows and quivers represented Cupid as instigator of God’s hope that love blossomed between two individuals. A broken arrow suggested a life, or a love, cut short. Trumpets were celebratory symbols, announcing the arrival of a soul into heaven. Another hopeful symbol was the combination of a cross, a heart, and an anchor, which suggested faith, love, and hope. These symbols often overlapped and combined with one another, illustrating that hope could be gleaned through faith, and vice versa.

Eyes were commonly found in jewelry and brooches, though not all brooches depicting eye imagery could be considered mourning brooches. For example, if there was no tear in the depicted eye, then the piece of jewelry was not a mourning token, but intended as a secret keepsake, to be kept by an individual in a clandestine romantic relationship. Hence, these tokens were often called "Lovers' Eyes".

Lovers' Eyes originated in 1785, when the Prince Regent, the future George IV, fell in love with the Catholic Maria Fitzherbert, but was forbidden to enter into matrimony with her due to the Royal Marriages Act. Consequently, after marrying Maria in secret, George wore a reproduction of her eye in a locket under his lapel, to keep her both hidden and close to his heart. He imagined that only a lover could recognize the eye of their better half, as a testament to the intimacy of their relationship. This sentiment soon became quite popular, and was fashionably adopted by other lovers who, like the young prince, commissioned miniature paintings of the eyes of their beloveds to keep on their persons.

Finally, even the numerous colours in mourning jewelry had inherent, respective meanings. The red and brown tones in sepia symbolized earth and blood, a combination of which was associated with death. Often, hair was crushed and added to these pigments. Blues were usually reserved for royalty, as was the crown motif. White symbolized the purity of the deceased’s eternal soul, and was predominately reserved for pieces commemorating children and unmarried women. White pearls perhaps represented tears, as some were worth nearly as much as diamonds. Black, naturally, was the obvious colour of mourning, and the ominous shade of gray was usually created with jet, a black, fossilized coral. For the first year of royal mourning in Victorian England, only jet or black enamel jewelry was worn by the grieving. The price and colour of gold testified to the wearer’s commitment and love for the deceased. Poorer families, for instance, would often pool their savings to purchase a gold brooch for a deceased relative.

2. Holm, Christiane. “Sentimental Cuts: Eighteenth-Century Mourning Jewelry with Hair.” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 38, no. 1, 2004, pp. 139–143. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30053632. Accessed 9 July 2020.

3. McMaster, Celeste. Review of Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture, by Deborah Lutz. Studies in the Novel, vol. 48 no. 1, 2016, p. 135-137. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/sdn.2016.0002.

4. Peters, Hayden. Art of Mourning – A Resource for Mourning, Memorial, Sentimental Jewellery and Art, artofmourning.com/.

5. Zhou, Zihan. “The Lover's Eye Jewelry.” 2019, doi: 10.25236/iwacle.2018.036.